Leading international publisher highlights UW-Whitewater student, faculty research on invasive plants

May 11, 2022

Written by Kristine Zaballos | Photos by Craig Schreiner

Cambridge University Press has published a study with implications for public and private land management strategies co-authored by Nic Tippery, an associate professor of biology at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, and two undergraduate researchers, Alyssa L. Olson and Jenni L. Wendtlandt.

The study, “Using the nuclear ‘LEAFY’ gene to reconstruct phylogenetic relationships among invasive knotweed (Reynoutria, Polygonaceae) populations,” was published in the Cambridge University Press journal Invasive Plant Science and Management.

Japanese knotweed (Reynoutria japonica) is one of the more troublesome invasive plants in North America, along with the related species giant knotweed (Reynoutria sachalinensis) and a hybrid between these species, known as Bohemian knotweed (Reynoutria × bohemica). Identifying the species and hybrids correctly is important, because not all species may respond to the same treatments such as herbicide and biological control. Moreover, if the knotweeds have a lot of genetic variation, this could enable them to become more invasive over time.

Nic Tippery, right, associate professor of biology, talks with students in front of a dense stand of Japanese knotweed, one of the more troublesome invasive plants in North America, near Whitewater Creek in Whitewater, Wisconsin, on Oct. 13, 2022.

In a project funded by the university’s Undergraduate Research Program, researchers Alyssa Olson and Jenni Wendtlandt identified distinctive DNA sequences in the LEAFY gene that could distinguish Japanese knotweed and giant knotweed, as well as hybrids.

During the research process, the team determined that each plant has up to three copies of the LEAFY gene. Some plants have a mixture of copies from Japanese knotweed and giant knotweed, allowing them to be identified as hybrids. The LEAFY data also showed that not all hybrids were genetically the same, with five different kinds of hybrids detected in Wisconsin.

The researchers then developed a relatively simple laboratory tool that can identify the types of LEAFY sequences in plant samples, using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). This tool can be employed relatively inexpensively to identify species and hybrids across North America and enable targeted control of invasive populations in municipal parks, golf courses, and on private property, among other areas.

“It’s been very rewarding to work on a high-profile project like this,” said Tippery. “Land managers across the state are eager to hear about our results, and there are legal implications for how these different knotweeds will be regulated. This tool can be employed relatively inexpensively to identify species and hybrids across North America and enable targeted control of invasive populations.”

Colin Topol, front, a biology major from Lombard, Illinois, takes a leaf fragment he has cut from a Japanese knotweed plant to begin the process of DNA sampling of the plant cells.

Study co-author Jenni Wendtlandt started at UW-Whitewater with a marine biology emphasis and moved into the ecology/evolution emphasis, which involved working with animals, trapping, and looking at data overall.

“We worked mostly in the lab; we went out to collect specimens once — usually people sent us samples that were collected in the wild. In the lab we were mostly extracting the DNA, amplifying it to make sure we had the correct sequence.”

Wendtlandt, who graduated in May 2020 with a degree in biology and a minor in environmental studies, is employed in dairy production in New Berlin, working in quality assurance, testing cheese and making sure results come back safe for the public.

“Being in a lab setting definitely helped with getting a job,” said Wendtlandt. “Employers want to know: How well do you work in a team? What kind of research have you done? That’s the benefit of a somewhat smaller school — you really get to know the professor you are working with one-on-one.”

“Having undergraduate students work on this kind of project means that they can gain visibility and relevant experience for future careers, and it underscores the high-quality work they can do,” said Tippery.

Nic Tippery, left, reviews the process of DNA sampling of Japanese knotweed fragments in the tiny vials with his lab team: Morgan Sabol, a biology major from Verona, Colin Topol, a biology major from Lombard, Illinois, and Jenna Boeck, a biology education major from Omro.

Since the study’s inception, other students have become involved in the ongoing research.

“In the past year, a new group of students — Morgan Sabol, Jenna Boeck, and Colin Topol — have more than doubled the amount of data we have for the LEAFY gene in knotweeds,” said Tippery. “We now have an almost complete DNA sequence for the gene, more than half of which was never sequenced in Japanese knotweed before. Having the additional DNA sequence data means that we can design additional tools for identifying knotweed species and hybrids.”

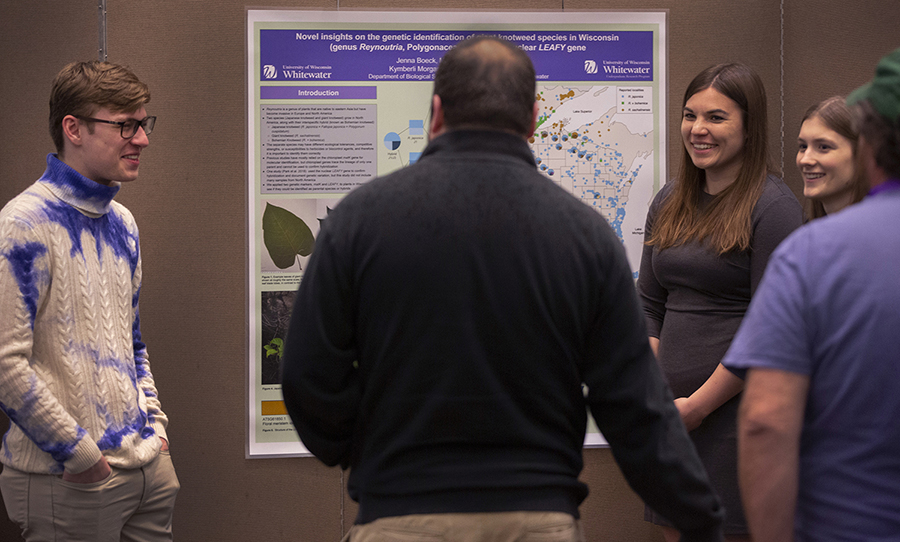

From left, biology majors Colin Topol, Jenna Boeck, and Morgan Sabol talk with Ozgur Yavuzcetin, back to camera, associate professor of physics, at a poster showing their research on giant knotweed at a UW System Undergraduate Research Symposium on the UW-Whitewater campus on April 22, 2022.

The recent breakthroughs propel the work of future students.

“This project will continue into 2022 and beyond, as we test additional samples from across Wisconsin and other parts of North America,” said Tippery.

For questions about the study or the biology program at UW-Whitewater, contact Nic Tippery, associate professor of biology, at 262-472-1061 or tipperyn@uww.edu.