John Frye

July 27, 2021

Written and photos by Craig Schreiner

In Great Teaching, John Frye, associate professor of geography, geology and environmental sciences, talks about choosing between two careers — meteorology and journalism — either of which might point him directly toward the eye of a storm.

Ultimately, Frye chose meteorology, a component he brings to the geography classes he teaches. When asked about inspirations, Frye will reply with no fewer than 10 names of teachers he had in high school, college and post-graduate studies. A field study led by one of those teachers inspired Frye to lead a 6,000-mile annual summer road trip through nine states that lets his UW-Whitewater students observe the weather conditions he talks about in the classroom. Frye strives to be accessible — willing to answer any question, passionate about what he teaches and concerned for the individual growth of students.

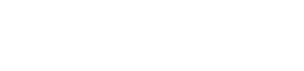

UW-Whitewater Associate Professor John Frye discusses tracking models of the area's first winter snowstorm with meteorology students in class.

“As a kid, I had a passion for both photography and weather. I followed those passions in a short career as a newspaper photographer and then as a professor in geography. I choose to teach because I want to have the same kind of an impact on students as all of my teachers and professors had on me. I teach physical geography classes related to meteorology, climatology, and environmental hazards. I like teaching here at Whitewater because of the focus on the teaching aspect of the job and also the smaller class sizes help to build relationships with students.”

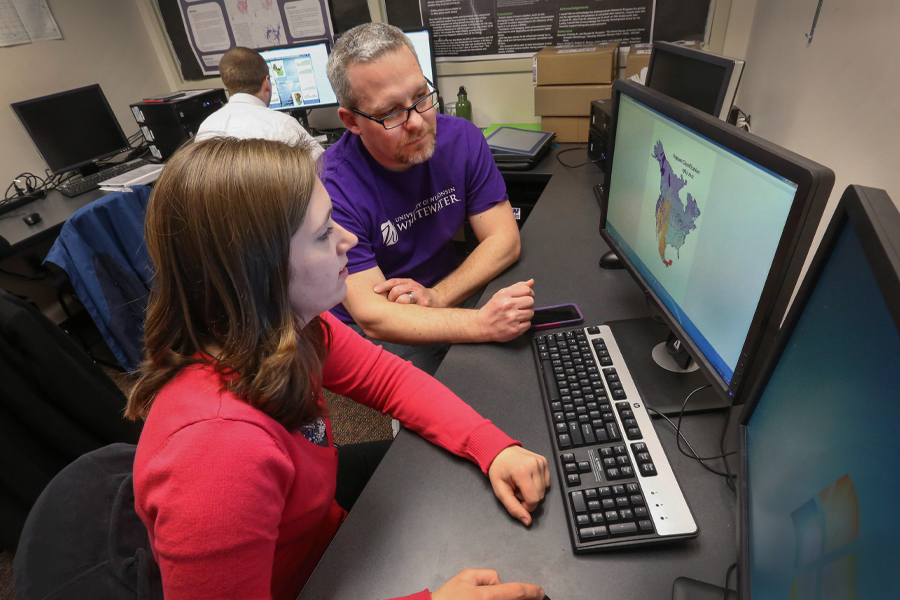

Geography major Ashley Vedvig looks at weather patterns with Associate Professor John Frye at Upham Hall.

“It is cliché, but it’s seeing the Aha! moment in students that is most rewarding for me. I get to experience this often with the field course I teach on severe weather. I felt the exact same way when I took a similar class almost 20 years ago. The classroom came to life in front of me and I learned so much on that trip with Dr. David Arnold. He was the one who encouraged me to come back to graduate school and pursue my master’s and then my Ph.D. He had a very strong influence on who I am today as a professor.”

Students on a field study led by Frye in the western U.S. observe weather conditions that they have been learning about in class. (Photograph by Associate Professor John Frye/UW-Whitewater)

“Throughout the semester the students learn about how to forecast and diagnose the atmosphere for severe weather,” said Frye. “The course concludes with a two-week field trip to the Great Plains to chase storms and visit locations that have been impacted in the past by severe weather. We see how they have rebuilt. Students take the textbook and background knowledge they have learned all semester and then see it in action in the field. And in the field, they learn things like how to be patient.”

“The first year I ran the storm chase trip at UW-Whitewater, about a week into the two-week trip, we had forecasted that storms would be occurring around North Platte, Nebraska. We got to North Platte around lunchtime and did an update of the weather conditions. This day wasn’t the best environment for storms but there was a chance, if we had some help from the “dryline,” which is a boundary between moist air and dry air. On the front side of the dryline, you’ll see small, white, puffy, cumulus clouds, and behind the dryline the air is dry and there are no clouds. As the hours ticked by, no storms were developing and the students were getting antsy. The dryline passed over our location, and still nothing. It had been a long day. I said we need to stay with this setup because it isn’t over yet, so we loaded up and headed east with the dryline.”

“Within 15 minutes, a classic low-precipitation supercell developed to our north and we were able to watch its evolution into the nighttime hours. It was a very photogenic storm, with a lot of rotation and lightning.”

“If you ask the students, they will most likely say it was the best day we had, even though we saw a tornado earlier on the trip in Texas. Everything we had learned in the classroom about the dryline was brought to life in front of them: diagnosing it on weather maps, watching it pass our location and feeling the conditions change because of it, and then watching this storm develop right along the dryline as we had discussed. It brought the classroom to life.”

(Photograph by Associate Professor John Frye/UW-Whitewater)

“I teach a wide range of undergraduate students in my general education lab science courses. I like hearing their perspectives on their various backgrounds and passions. In my upper-level classes I mainly teach environmental science and geography students who are pursuing careers as GIS technicians, environmental consultants, and students looking to pursue graduate work, to name a few.”